Sociology — 1960–1980

Wicked Problems and the Design Business

Sociology

George Orwell described the ideological battle between capitalism and socialism as a “cold war.” Sociology in its various forms — politics, social systems, communication, and meaning — impacted the practices of design during this period. Politics was ever present in the application of design through laws, policies, as well as public need. Design Methods began as a response to complex problems, and manifested in a realization that Wicked Problems required not only new skills, but new thoughts about who should design and how solutions were applied to communities. Consumerism, and global business growth, continued to perpetuate a blend of marketing and design in the United States resulting in the need for design to become a big business itself. Design offices like Unimark and Pentagram emerged to serve these corporate clients. Viktor Papanek and Ralph Nader brought the conversation about the societal impacts of design — social design — to the foreground. Design went through the same social changes that impacted society at large.

Image above: Ralph Nader (Fia Foundation)

Header image: Unimark International Staff

Assignments for the Class

Readings & Assignments

The readings for the week include the following:

ASSIGNED READING — Primary: A Short, Grandiose Theory of Design, Jay Doblin, 1987 (STA Design Journal)

ASSIGNED READING — Research: The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research, 1979 (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services)

SUPPLEMENTAL READING — Design Education: The India Report, Charles and Ray Eames, 1958 (National Institute of Design, India)

Assignments for the week are as follows:

Product Portfolio

Locate a relevant and impactful product from the period we are discussing (1960-1980). Discuss:

Why does the product exist and what needs were met?

Why is the product important?

Who did the product empower/disempower?

What behaviors did the product change or create?

Method Toolkit

AEIOU (The Design Context):

Identify a context and task that you can observe

Visit the context and observe people interacting to complete the task

Fill in a worksheet with observations which correspond to the AEIOU framework

Identify an insight or two on the context of the experience

Here is a LINK describing the method, but look for some others

The Context

George Orwell coined the term cold war as a state of perpetual conflict. It began with the close of WWII. By 1960, the cold war divided the world into spheres of influence. The United States had experienced a decade of rapid economic growth in the 1950s, and suburban growth drove an era of consumerism. Nuclear war and the ability to experience the challenges faced around the world through media brought about a recognition of a new class of problem. Wicked Problems were so complex that defining them was impossible. The global standoff between the two spheres of influence persisted until the fall of the Soviet Union between 1988-1991.

Image right: The Kitchen Debate (1959)

Socially Responsible Design

“Advertising design, in persuading people to buy things they don’t need, with money they don’t have, in order to impress others who don’t care, is probably the phoniest field in existence today.”

Viktor Papanek

Health and mortality improvements helped humanity begin to expand at rates beyond our historic rates. The increases in the world population during this period are notable. In addition to the population trends, feeding the world was to become a “wicked problem” on its own.

Source: Our World in Data

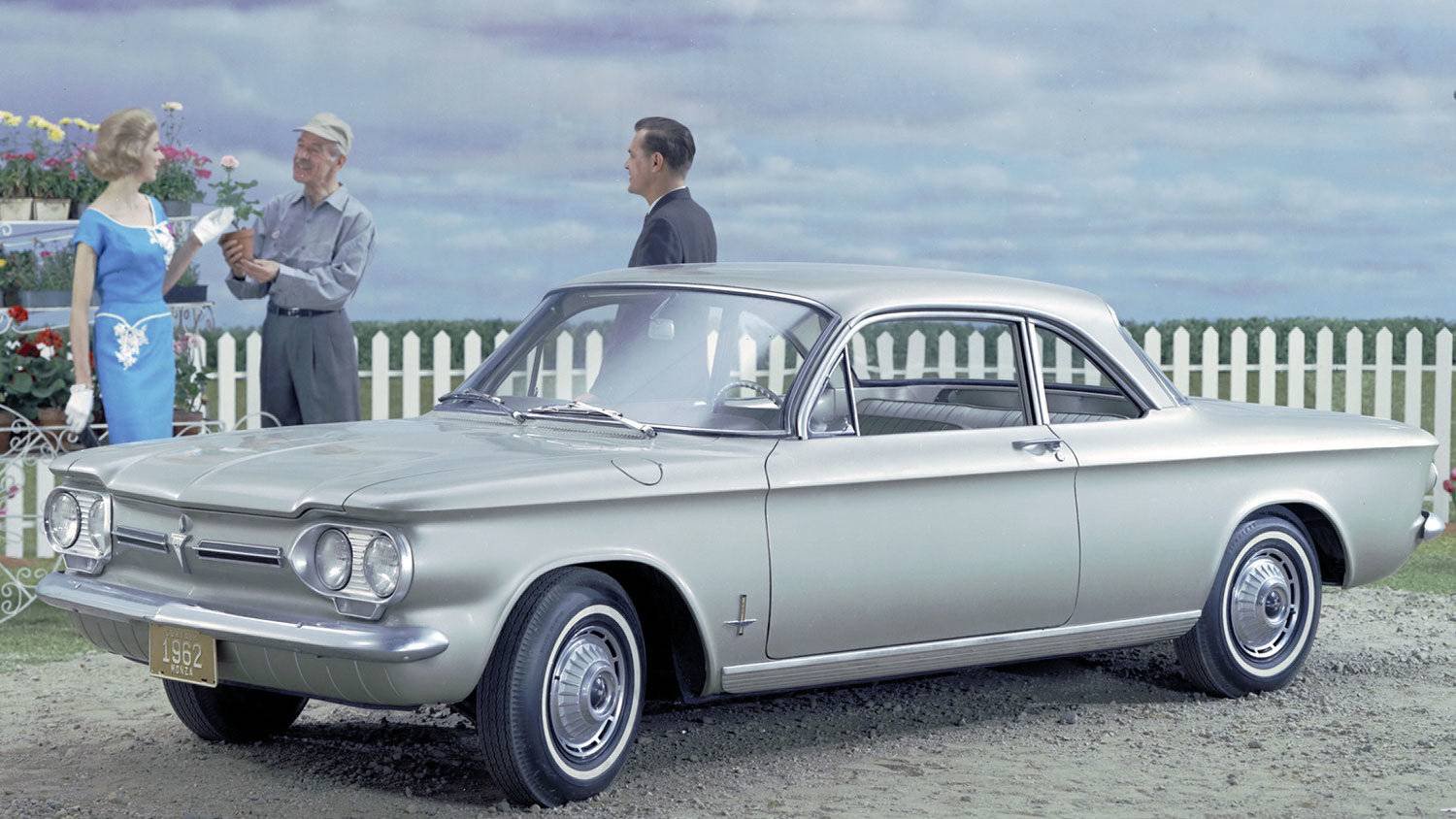

Unsafe at Any Speed

In addition to safety, Ralph Nader’s 1965 book Unsafe at Any Speed discussed topics including: usability issues, pollution, driver education. The conversation brought the 30,000+ vehicle fatalities that occur each year to the forefront. Automobile styling over the substance of safety was particularly critiqued by Nader. While safety has improved in the United States, it remains an issue in less regulated countries.

“Pressure on car manufacturers is growing. The World Health Organization’s Global Status Report on Road Safety 2015 recommends that all countries should require, at minimum, that all cars sold should meet a set of seven basic UN standards including crashworthiness performance, pedestrian protection and provision of electronic stability control.”

The auto industry avoided features which added cost to vehicles. Those who supported safer products responded, that all automakers would face the same cost increases. Still, adding costs would inhibit the consumer from treating the auto as an easily replaceable purchase. With increased auto traffic, safety was also a concern communities.

Image right: Unsafe at Any Speed book cover

Chart above: US vehicle deaths 1921-2017

Design for the Real World

Viktor Papanek wrote Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change in 1971. Echoing Buckminster Fuller, Papanek believed the design should serve people, and that the world had finite resources, which is shared would meet everybody’s needs. He hoped to address systemic challenges in the design profession including:

The purpose of design

Renewed consideration of indigenous solutions

Ecologically sound design

Papanek was largely condemned by the design community for pointing out these failings of the profession. He felt that designers contributed to three primary activities which had adverse affects on society:

Designing things people do not need, supporting consumerism

Killing people with unsafe products

Depleting resources, adding to waste, and polluting the air.

Source: Furthering Victor Papanek’s Legacy: A Personal Perspective, Cees de Bont (She-Ji)

Image left: Design for the Real World cover

“Papanek introduces five myths that exist in the design world (and equally viable alternatives): the myth of mass production (small series are needed to accommodate for diversity), the myth of obsolescence (repairs are viable if products are well designed), the myth of people’s wants (we seldom check our assumptions), the myth that designers lack control (designers should question projects), and the myth that quality no longer counts (companies that make high quality products tend to survive). In spite of his criticism of the work designers are doing, Papanek is kind enough to admit that many consumer products are designed with sensitivity and skill in the category of performance products, such as camping products and cooking utensils.”

Cees de Bont from “Furthering Victor Papanek’s Legacy: A Personal Perspective” (She-Ji)

The Belmont Report

The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, Report of the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research was published by the by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research in 1979. It establishes ethical principles and guidelines for research involving human subjects and was a response to unethical studies including the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932–1972). The report identifies three core principles including: respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. The report also describes thee areas of application:

Informed consent

Assessment of risks and benefits

Selection of subjects

The ten page report is required reading fro any student wishing to work in the medical field or in research environments.

Source: Wikipedia

Image right: The Belmont Report

John Lennon and Yoko Ono with a white bike in Amsterdam in 1969 (Bloomberg)

Thoughts to Consider

Consider the regulations and laws that impact designers.

Image left: President Nixon signing the Occupational Safety and Health Act, 1970

Systems Problems

“Synergy is the only word in our language that means behavior of whole systems unpredicted by the separately observed behaviors of any of the system’s separate parts or any subassembly of the system’s parts.”

Buckminster Fuller

Approaches to Systems Problems

Many of our persistent problems are systemic in nature — war, poverty, education, civil rights, etc. Developing “Systems Literacy” and developing approaches to interacting with complex systems is a requirement for designers who intend to impact the world in a positive manner. C. West Churchman, an American systems scientist, believed that many decision-makers lacked the foundations from which to make informed decisions on complex issues. He outlined four to systems problems:

The approach of the efficiency expert (reducing time and cost);

The approach of the scientist(building models, often with mathematics);

The approach of the humanist(looking to our values); and

The approach of the anti-planner (accepting systems and living within them, without trying to control them).

We might also consider a fifth approach: The approach of the designer, which in many respects is also the approach of the policy planner and the business manager, (prototyping and iterating systems or representations of systems).

Hugh Dubberly describes three steps to achieving systems literacy. Firstly, designers must develop a vocabulary of systems topics. Secondly, we need to nurture a capacity to analyze systems and problems. And lastly, designers must ultimately synthesize and describe both existing and imagined systems. Our intention is to raise awareness of these topics and relevant readings so that design students can develop their literacy of the topics.

Image right: Negative feedback loop diagram (DDO)

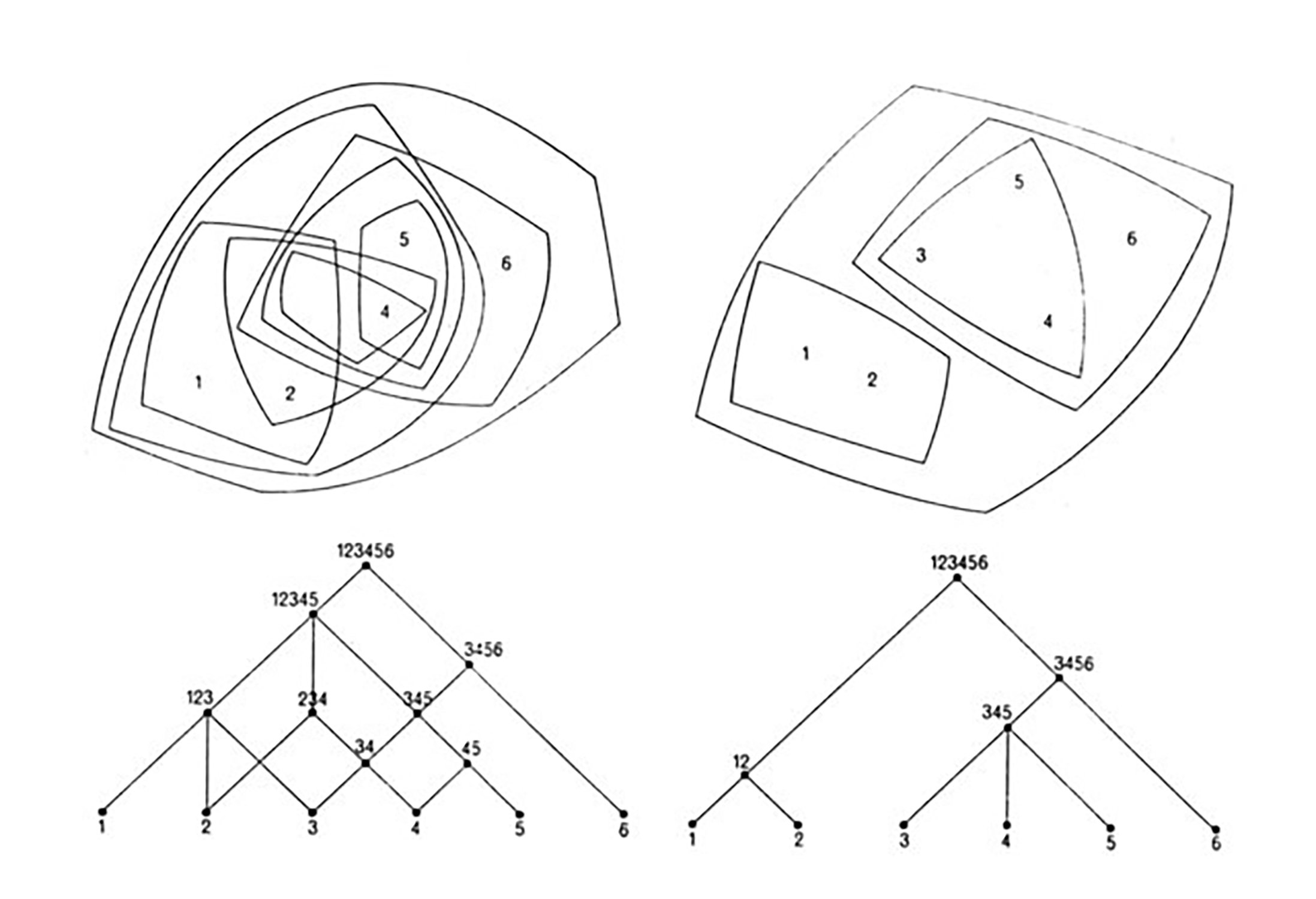

Diagram: from “A City Is Not a Tree” by Christopher Alexander, 1965

“Diagrams of Semi-Lattice (left) and Tree (right). According to Alexander (1965), ‘It is not merely the overlap which makes the distinction between the two important. Still more important is the fact that the semi-lattice is potentially a much more complex and subtle structure than a tree.’”

The Information Department

Max Bense had been a guest lecturer of “Aesthetics” at the HfG Ulm since the beginning in 1953. He had begun to develop an experimental curriculum focused on “information and communication.” In an information brochure from 1955 the program becomes more articulated:

“The Information Division, yet in an evolutionary state, is concerned with the problems of information and communication. Its sphere of action ranges from simple press reports via advertising and broadcasting to the results of cybernetics.”

Utilizing the scientific foundations of semantics and information theory, Bense brought an intellectual base upon which to build practical information artifacts. The conflict between science and intuition mirrored the larger conflicts at the school. The space between advertising and topics such as Cybernetics was incredibly broad.

New system of signs (1963), Tomás Maldonado, Gui Bonsiepe

The Whole Earth Catalog

“The Whole Earth Catalog, first published in 1968, can be considered the bible of counterculture in the 60s and 70s.” Not only was it a guide for creating and hacking one’s environment, it was a tool for empowering individuals to learn and do themselves. “Tools” were considered to be both physical in nature, as well as mental frameworks.

Stay Hungry. Stay Foolish.

The Whole Earth Catalog ceased publication in 1971, but it’s influence extended to the maker culture in Silicon Valley as well as to future publications like Wired.

Image left: Page from the Whole Earth Catalog (Doors of Perception)

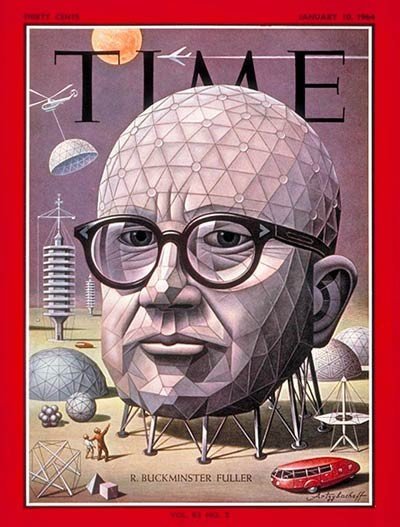

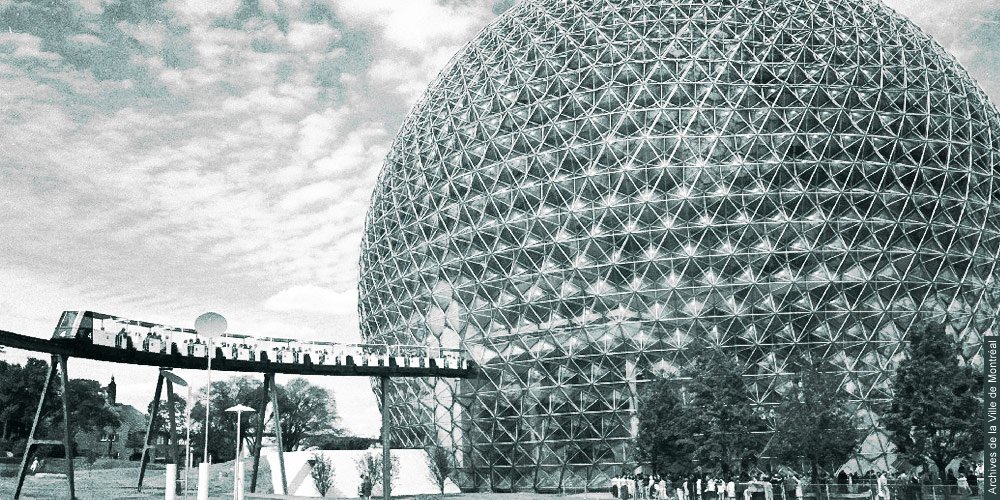

Spaceship Earth

Buckminster Fuller called himself a “comprehensive anticipatory design scientist” and believed that our resources were limited on this ship we call planet earth. Yet, with these resources, we are fully capable of providing for everybody on our ship. The artifacts he created represent the possibility of living life to the maximum while utilizing fewer resources.

What does Dymaxion mean, anyway?

It was originally conceived by an adman who wanted to interest people in Fuller’s house, which he called the 4D House. The adman listened to him rambling and ranting and kept hearing him saying "dynamic" and "maximum" and "tension" over and over. So the ad man thought of “dymaxion.” And Fuller applied the word to absolutely everything that he did. It became kind of his personal trademark.

Fuller best represents the idea of experimentation in design. The article referenced here notes the evolution from mapping to the “geoscope” to the geodesic dome. The path was not clear. Guided by principles, Fuller found new uses for his ideas as they evolved. Participation in this adventure was not an economic motivation. As he noted, “You can make money or you can make sense. The two are mutually exclusive.”

Image left: Time Magazine with Buckminster Fuller (ArchDaily)

Sources and image below: Buckminster Fuller with The Biosphere (Wired)

Thoughts to Consider

Consider how systems and resources impact design.

Image left: Earth Day Flag (Wikipedia)

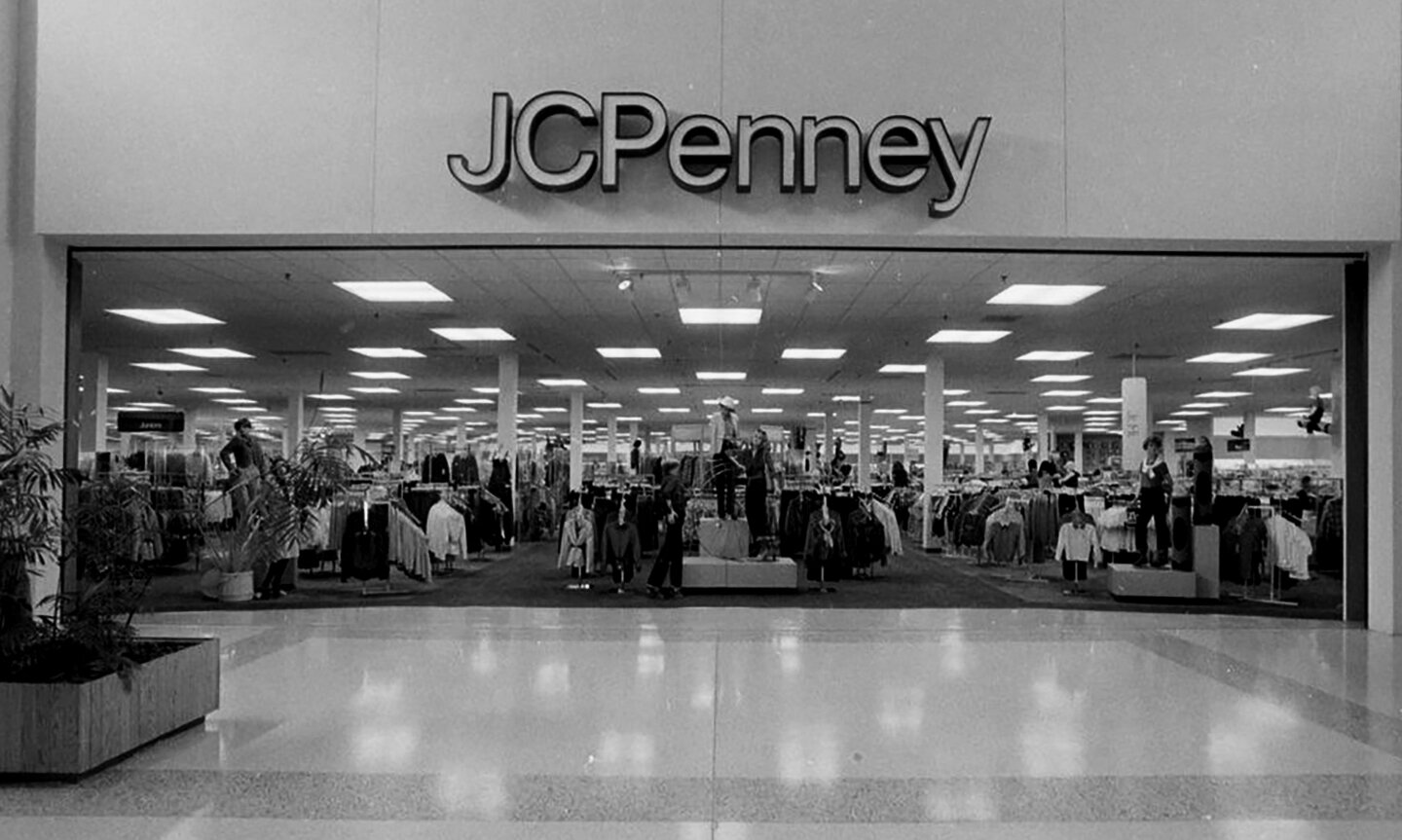

Unimark International

Unimark International was founded in Chicago in 1965, with two additional offices in New York City and Milan. Ralph Eckerstrom, Massimo Vignelli, Bob Noorda, James Fogelman, Wally Gutches, and Larry Klein were the founding partners, although Jay Doblin and Robert Moldafsky were brought in very quickly. The firm rapidly are beyond the original three offices, ultimately leading to challenges during the recession in the early 1970s. A focus on marketing science and European design brought much success, but also challenges in recruiting new clients. Clients included American Airlines, Ford, JCPenny, the New York Transit Authority, and Target.

Target Identity (1962)

from DesignIssues: Volume 27

“No matter how rationally and systematically pursued (and Unimark was as rigorous as any in this regard), even the most profes- sional design approach remains too loosely defined, and the visual abstraction of its medium too arbitrary, to ever fully resolve into the tool for clear, direct and global communication that it vies to become.”

Brian Donnelly

Pentagram

Design firms began to consider the skills they assembled differently as business needs changed. Local clients may provide the bulk of the work, but serving global businesses became the aspiration. As with Unimark, Pentagram sought to unify and collaborate, but modeled the firm after business consulting groups.

“Most design firms, whether graphic, product or architectural, have grown from the creative and entrepreneurial energy of an individual or two or three partners. Historically, only one or two out of thousands has ever continued into a second generation. The design-driven offices of George Nelson, Charles and Ray Eames and Eliot Noyes disappeared with the death of their founders. Practically the only design firms to survive beyond the first generation have been marketing-driven companies like Lippincott & Margulies and Walter Dorwin Teague. Yet if you consider dominant names in other service industries, Arthur Andersen or Peat Marwick in accounting, for example, or McKinsey or Deloitte in management consultancy, they have all reached their second or third generation. The size and success of these organizations makes it hard to relate their experience to relatively miniscule design firms, but I believe we still have something to learn from them. The challenge is to run what we believe to be an excellent design-driven firm into a second generation.”

Establishing a Pentagram “culture” and educating every partner in the workings and strategies of the firm was critical to powering the business beyond the founders tenure. Public relations and business development was both a common activity and a partner directive. Running the office as a business was essential. Pentagram continues to be a strong example of a successful design business.

Source and image left: Campaign poster, 1970 (Pentagram)

The Action Office

The Action Office was created by Robert Propst under George Nelson’s supervision. The office furniture was introduced by Herman Miller in 1964 in its first iteration. Action Office I was intended as an “semi-enclosed office” environment, while the second iteration introduced the “cubicle” concept to the world of work. Substantial research into the evolution of the office, as well as consultations with the University of Michigan on topics such as learning and communication informed the project. “Propst concluded that office workers require both privacy and interaction, depending on which of their many duties they were performing.”

Criticism of the ultimately successful cubicle design has been levied by Propst and others. The dehumanizing affects of these modular environments are persistent from the inception of office work and concepts of what constitutes “productivity.” The conversation of what office managers would accept from a designed product are also interesting. The Action Office I is surprisingly modern.

Image right: Action Office I, Robert Propst, 1964 (George Nelson Foundation)

Braun

Dieter Rams won a competition with a co-worker to apply for a job with a little known manufacturer in Frankfurt. Artur and Erwin Braun managed the business and were forward thinking in their hope to create new products for consumers. Design was intended to support the marketing of products as well as to create additional value. Braun created partnerships with HfG Ulm and Hans Gugelot prior to the arrival of Rams. The collaboration was fruitful and the separation between contributors is often difficult to separate. Rams believed that the function and use of the product should be obvious. The design of elements such as the speaker grill of the TP1 is a powerful testimonial to Rams’ attention to detail. Braun was truly the Apple of its time, and Rams the influence of Jony Ives.

Image left: Braun TP1 Radio and Record Player (Braun)

Dieter Rams on

Ten principles for good design:

Is innovative

Makes a product useful

Is aesthetic

Makes a product understandable

Is unobtrusive

Is honest

Is long-lasting

Is thorough down to the last detail

Is environmentally friendly

Involves as little design as possible

Plastic shell suitcases (1965-66), by Dieter Raffler and Peter Raacke, image: HfG-Archiv/Ulmer Museum

Thoughts to Consider

Consider why design became uniquely important to business.

New York City Transit Authority signage system (1970), Unimark

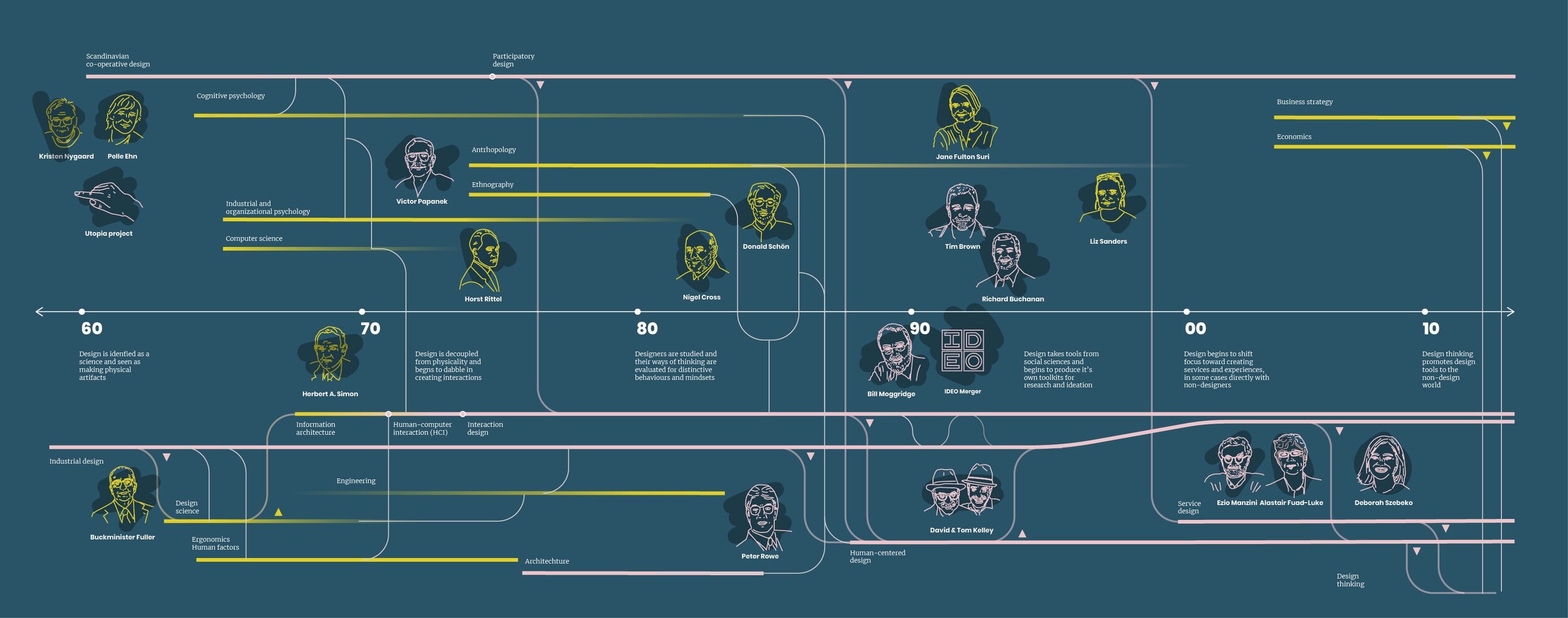

The origins of design thinking, Jo Szczepanska