Topic: Systems Design

From Wicked Problems to Improving Complex Services

Systems Design

With the new perspective of our planet provided by space exploration, humans began to think about our home in new ways. It wasn't simply a resource to be used, but was a fragile ecosystem floating in space. The formulation of Wicked Problems and the growing list of problems which seemed beyond our control provided new opportunities for designers to explore. There were bigger problems to solve than designing consumer products, and some designers began to think big. The Limits to Growth (LTG) report was published in 1972 by Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III. The report was influential in promoting environmental reforms. Donella H. Meadows later wrote Thinking In Systems: A Primer, which was posthumously published in 2008. Designers engaged with complex problems must learn to engage with systems to influence change.

Image above: The Business-as-usual Scenario (Ecological Economics for All)

Header image: Earthrise, William Anders, 1968 (Wikipedia)

Assignments for the Class

Readings & Assignments

The readings for the week include the following:

ASSIGNED READING: Algorithms of Behavior and Behavior of Algorithms: A Conversation between Ashish Jha and Patrick Whitney, by Mo Sook Park, L Fahn-Lai, Reena Shukla, André Nogueira, and Patrick Whitney, She Ji, 2022

The assignment for the week is as follows:

Team Project

Research with students using two (2) Systems Design frameworks:

Select systems design framework to understand what goes into design education

Who are the stakeholders?

What pieces go into the holistic system?

The link above to IDEOU has ideas to consider

What is the context of our class and design education?

You own the board. Make something interesting and think about sharing with others

Ideally work in pairs to reduce work but communicate what you find

Systems Theory

“Dynamic systems studies usually are not designed to predict what will happen. Rather, they're designed to explore what would happen, if a number of driving factors unfold…”

Donella H. Meadows, Thinking in Systems, 2008

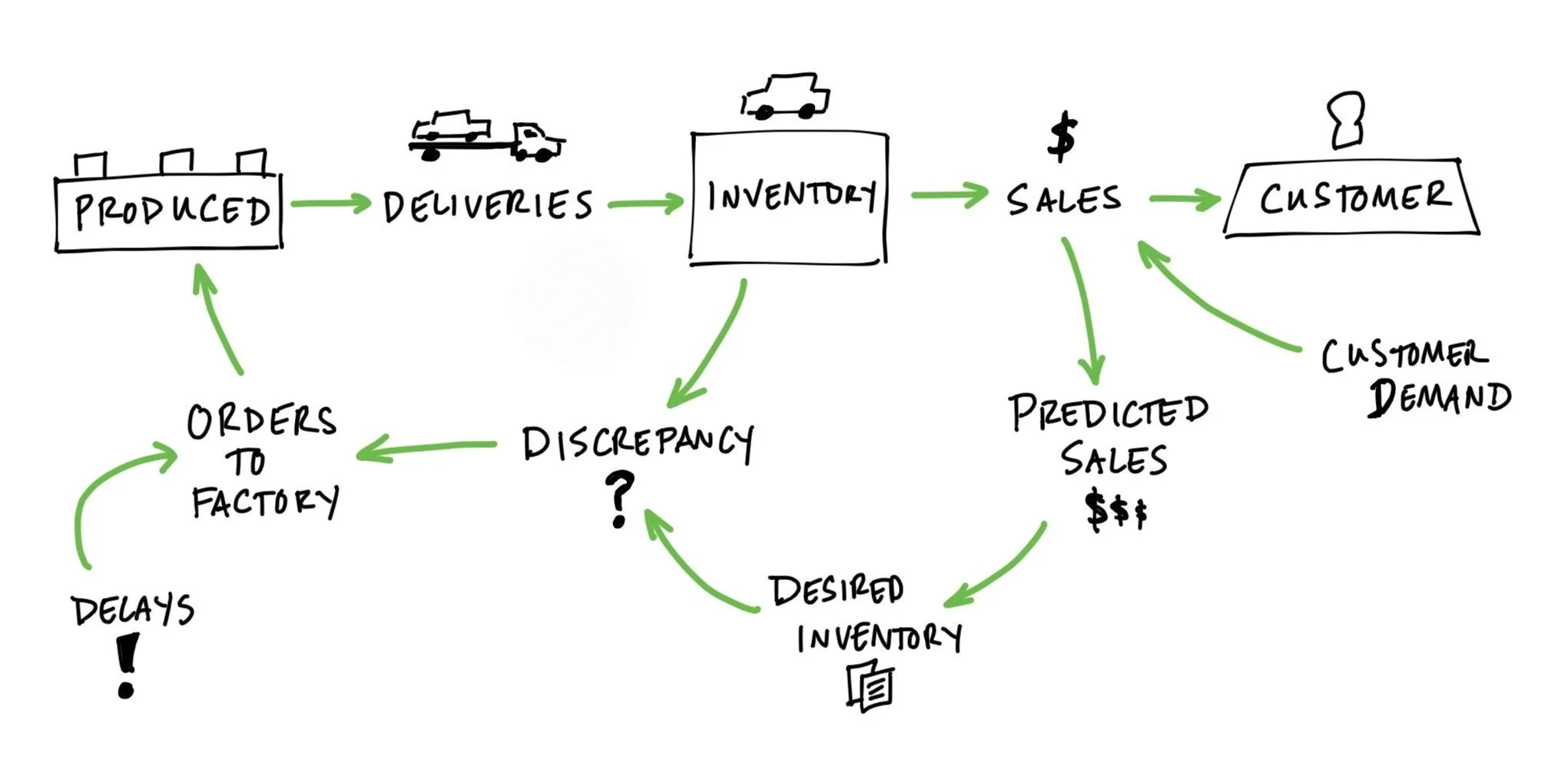

As Donella Meadows describes, “A system* is an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something. If you look at that definition closely for a minute, you can see that a system must consist of three kinds of things: elements, interconnections, and a function or purpose.” In the diagram above we can see the elements which may be systems themselves. We can fathom the connections in trucks arriving with shiny new cars. And, we identify the purpose from a couple of perspectives. One might be Henry Ford trying to build and sell automobiles. The other might be, consumers wanting to purchase new cars. Many things can go wrong as recent history has demonstrated. What are some challenges posed by this system?

Image above: Car production, in reality (Coleman McCormick)

Image below: BYD e6 all-electric taxi in Shenzhen, China (Wikipedia)

Origins of Systems Thinking

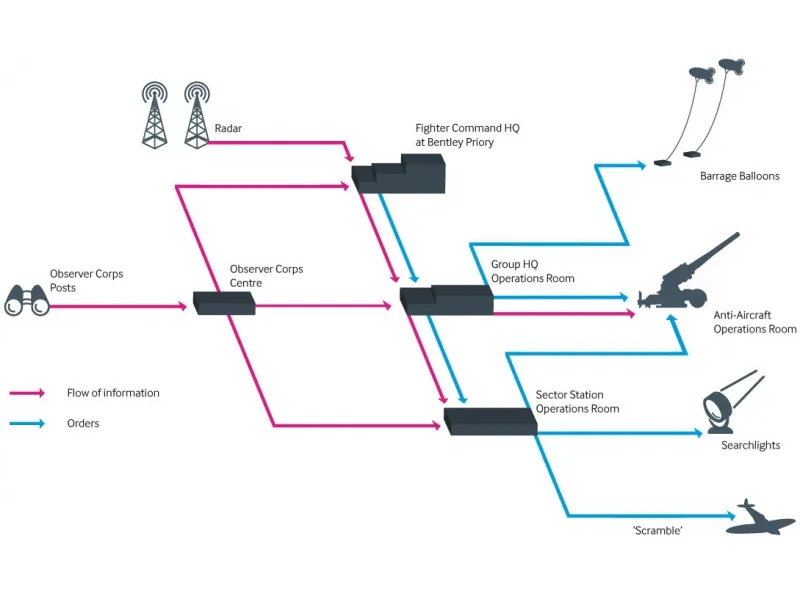

Communication, operations, and command are central to modern warfare. WWII brought new needs to global conflicts. Simple logistics are critical to keeping an army together. The war brought new tools to support the war effort including Operations Research, and Cybernetics. The diagram at right demonstrates how the Dowding System integrated communication and tools like radar into a defensive network.

“The British had developed an air defence network that gave them a critical advantage during the Battle of Britain. The Dowding System – named for Fighter Command’s Commander-in-Chief Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding – brought together technology, ground defences and fighter aircraft into a unified system of defence. It not only controlled the fighter force, but other elements of the defence network as well, including anti-aircraft guns, searchlights and barrage balloons.”

These new tools and modes of thought were applied to complex problems both during the war and after. As our view of the world and understanding of complex problems grew, they were applied and adapted to topics such as poverty, policy, and environmental issues. As the tools propagated, the foundation principles remained relevant.

Image right: Diagram of the Dowding System (Imperial War Museum)

Why Systems Thinking?

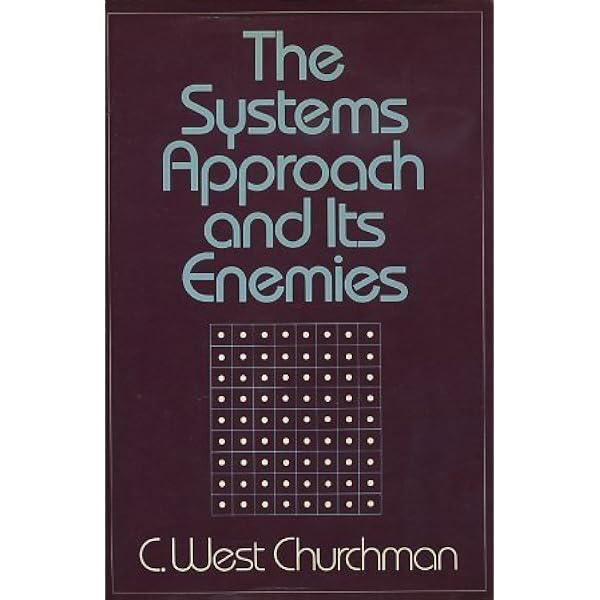

Hugh Dubberly shares a C. West Churchman quote in his article “A System Literacy Manifesto,” “…there is a good deal of turmoil about the manner in which our society is run. …the citizen has begun to suspect that the people who make major decisions that affect our lives don’t know what they are doing.” This was in 1968, and Donald Schön provides similar thoughts about professionalism during this period. Churchman described 4 enemies of an approach to systems that considered diverse viewpoints. These are:

The Efficiency Approach (Politics): Focuses on identifying and removing waste or unnecessarily high costs within a system. Churchman noted that this approach, while important, can oversimplify the purpose of a system and often runs into political challenges during implementation.

The Scientific Approach (Morality/Ethics): Advocates for an objective, model-based view of the system, often using mathematics, economics, or behavioral science. This approach aims to understand how the system works but can fail to capture human values.

The Humanist Approach (Religion/Aesthetics): Claims that systems are fundamentally about people and prioritizes human values like freedom, dignity, and privacy. Humanists often argue against imposing rational plans that might override these personal aspects.

The Anti-Planners Approach: Believes that any attempt to create a single, comprehensive, rational plan for a complex social system is foolish, dangerous, or evil because the systems are far too complicated for our current intellectual powers to fully understand.

Dubberly reflects on these four “enemies” and provides a fifth designerly approach.

“Churchman outlined four approaches to systems: 1) The approach of the *efficiency expert* (reducing time and cost); 2) The approach of the *scientist* (building models, often with mathematics); 3) The approach of the *humanist* (looking to our values); and 4) The approach of the *anti-planner* (accepting systems and living within them, without trying to control them).[12] We might also consider a fifth approach: 5) The approach of the *designer*, which in many respects is also the approach of the policy planner and the business manager, (prototyping and iterating systems or representations of systems).”

As designers, you will encounter the challenges presented by systems as well as managers of systems. As we saw during the Design Methods Movement, designers themselves can present these perspectives. Embracing complexity is the first step towards engaging in systems thinking.

Source for indented, bulleted text: Google AI

Image left: “A Systems Approach and Its Enemies” book cover

How Systems Work

The behavior of systems can be described using a few simple elements. Stocks are comprise of a store of materials or information. Flows reflect the changes in stocks over time, through the inflows and outflows of material in a stock. Dynamics represent the behavior of a system over time. Feedback allows a system to be regulated or to self-regulate. The representation of systems help people to understand the essential behavior and what elements are important to how the system functions relative to its purpose.

Designers have specific strengths which allow them to add value to conversations about systems. The ability to abstract representations of systems is critical to facilitating effective conversations. Collaboration across disciplines enables strong generalists to provide the human, behavioral perspective which is necessary to supporting systemic change. There are a number of points to leverage in order to influence change in systems.

Image right: Diagram of a negative feedback loop (Dubberly Design Office)

Leverage Points in Systems

Meadow’s twelve leverage points to intervene and institute change in systems:

Transcending Paradigms

Paradigms—The mind-set out of which the system—its goals, structure, rules, delays, parameters—arises

Goals—The purpose or function of the system

Self-Organization—The power to add, change, or evolve system structure

Rules—Incentives, punishments, constraints

Information Flows—The structure of who does and does not have access to information

Reinforcing Feedback Loops—The strength of the gain of driving loops

Balancing Feedback Loops—The strength of the feedbacks relative to the impacts they are trying to correct

Delays—The lengths of time relative to the rates of system changes

Stock-and-Flow Structures—Physical systems and their nodes of intersection

Buffers—The sizes of stabilizing stocks relative to their flows

Numbers—Constants and parameters such as subsidies, taxes, standards

Image: From How Design Affects Health, by Joy C. Liu, MD, MPH. (AMA Journal of Ethics)

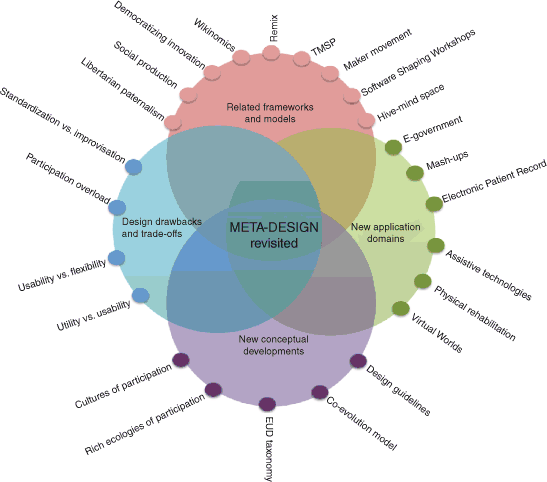

Metadesign

“It is the design of the parameters of a system... the limit of the possible configurations of the elements,... We will call the design of this visual-formal language meta-design.”

“Metadesign,” Andries van Onck, 1965.

Metadesign

Metadesign was proposed by Andries Van Onck, while at Ulm School of Design in 1963. It is a framework for promoting collaborative design (co-design) and eliciting participation not only from designers but from individuals and communities. Systems are utilized to propose solutions. The framework has been elaborated upon to include a set of tools that are used by designers.

“Metadesign is a set of four cognitive tools: (a) diagram; (b) abstraction; (c) emergence; (d) procedure.”

The Metadesign expands upon system design to include users in the conversation about what problems exist, the possible solutions, and what is ultimately delivered for use.

“Meta-design is an emerging conceptual framework aimed at defining and creating social and technical infrastructures in which new forms of collaborative design can take place. It extends the traditional notion of system design beyond the original development of a system to include a co-adaptive process between users and a system, in which the users become co-developers or co-designers. It is grounded in the basic assumption that future uses and problems cannot be completely anticipated at design time, when a system is developed. Users, at use time, will discover mismatches between their needs and the support that an existing system can provide for them. These mismatches will lead to breakdowns that serve as potential sources of new insights, new knowledge, and new understanding.“

Rather than react to the cognitive dissonance presented by the application of design methodologies to real world problems, Metadesign proposes solutions that incorporate new insights and emergent innovations into the process. Evolutionary growth becomes a tool for use by design teams, using new models for applying the tool to problems through tools such as SER — “Seeding, Evolutionary Growth, Reseeding (SER) Model, a process model for large evolving design artifacts.” Design systems become sets on components to be used as the solution “organism” emerges and grows. Designer propositions and visualizations provide both ideas and solutions in the problem context. Participation through co-design becomes a necessary model of design, requiring that designers facilitate design, and act as gardeners within the problem space.

Quotations: “Design and Politics: Metadesign for social change,” Caio Adorno Vassão, 2017; Meta-Design: A Framework for the Future of End-User Development, by Gerhard Fischer and Elisa Giaccardi, University of Colorado, Center for LifeLong Learning and Design (L3D) in Lieberman, H., Paternò, F., Wulf, V. (Eds) (2004) End User Development - Empowering People to Flexibly Employ Advanced Information and Communication Technology, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

Image left: The Meta-Design Framework from Revisiting and Broadening the Meta-Design Framework for End-User Development, New Perspectives in End-User Development, Gerhard Fischer, Daniela Fogli & Antonio Piccinno (Springer Nature)

Metadesign

“We were partners in Berlin and London back in 1979, and MetaDesign was both a reference to the metric system that we were using in Germany, but that the Brits hadn’t quite embraced properly (as in milli-meta!), and the fact that we were doing design for design, i.e. instructions for other designers [on] how to use the rules of corporate design systems that we developed. And design for design is metadesign. The CenterCap was just starting to become fashionable, so MetaDesign.”

Eirk Spiekermann (Dubberly)

Thoughts to Consider

Can emergent design be a useful approach?

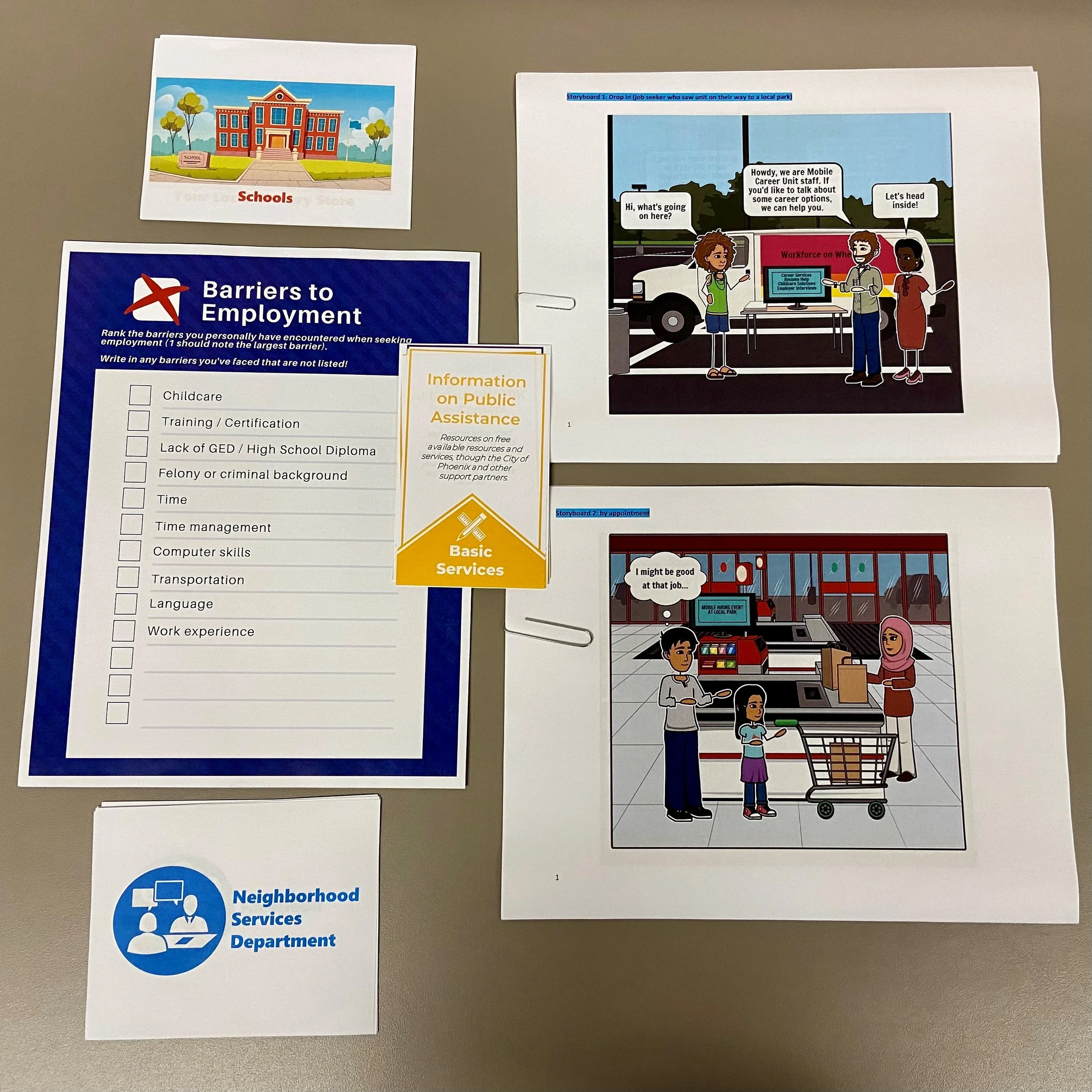

Image left: Bloomberg Cities artifacts (Nicholas Paredes Studio)